Ruth Maclennan

April 9 to April 16

Last night the spring tide was so high the sea filled the whole bay, covering the beach and submerging the ruined harbour. It made me think of all the human structures now covered by the sea, invisible and forgotten. Today the waves were still strong and crashing (not good for surfing, Sasha told me). The seabirds – kittiwakes, fulmars, oyster catchers – were excited, flocking along the caps of the waves where fish were being churned up to the surface. Scatterings of puffins bounced along the surface of the waves far beneath us. We stepped carefully along the cliffs in the bright sunlight, a warmer westerly wind blowing in our faces as we hung close to the fence only a few steps from the edge. I prefer going first so I can’t see others walking and worry about them losing their footing and imagine the horror of them falling.

April 2 to April 9

///cheeses.quarrel.poorly is the WHAT3WORDS location of Peedie Sands in Caithness, Scotland.

58°40′21″N 03°22′31″W

February 12 to March 19

These seeds were given to me by the farmer who grew them, on a small but vibrant organic farm in South Korea. They grow organic cabbages and mouli for Kimchi, and propagate local native species, which have been in decline, distributing them to local farmers. I can’t remember which seeds are which. These tiny envelopes are full of anticipation and hope, dormant but ready to sprout if I let them. We were filming scenes for Delicious Revolution, a film about food cultures, and how to transform food systems around the world for human and planetary health. https://www.deliciousrevolutions.com/

February 27 to March 5

An ecosystem is a peculiar kind of self-organizing archive – a collection of interconnected things rubbing along together, reliant on each other, connected with other organisms and systems, adapting to changing environmental conditions, or dying. This wild archive (that might well be touched by humans but behaves according to non-human rules) has a history too. Recognizing and appreciating the unruly, unpredictable, historical instances of natural adaptations can help us understand how to thrive in turbulent times. Ironically perhaps, strict protection rules – human laws and treaties – are needed to enable these wild archives to survive. Marine Protected Areas for research and conservation for example. Archiving the wild isn’t quite what I mean. The seed vault in Svalbard cannot contain all the conditions that will enable the seeds at some future date to germinate and produce crops and reproduce the ecosystems they came from. It is useful perhaps, but won’t save us.

[from my chapter, ‘An Artist unpacks the Archives’, in Archives: Power, Truth, and Fiction, edited by Andrew Prescott and Alison Wiggins, Oxford University Press, 2023, p 417].

February 13 to February 20

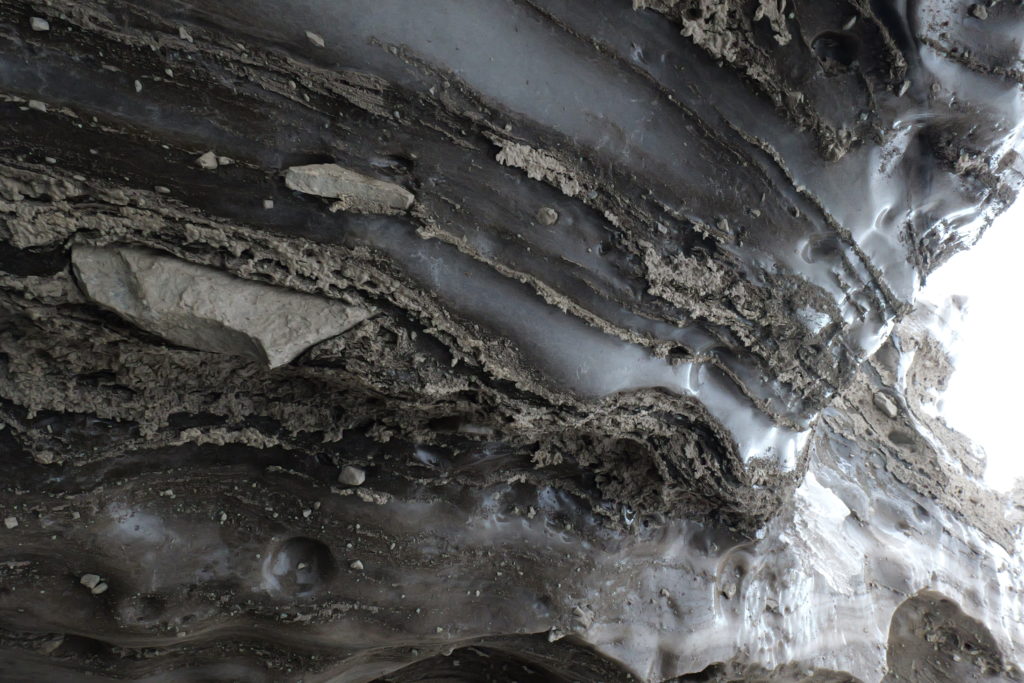

These layers hold centuries of air bubbles suspended in ice, pressed between layers of compressed rubble and coal dust. This moving archive speaks of changes in weather and climate, to those who are able to decipher it. This is Larsbreen, one of the glaciers above the town of Longyearbyen, and it is dying. I could say it is shrinking, but that’s not what the glaciologist, Léo Décaux said. He told me that Larsbreen is dying, silently. There isn’t enough snow to compact into ice, and summer temperatures have increased so much that melting ice isn’t replaced or refrozen. The glacier is melting from above and below. This glacier doesn’t reach the shore anymore so its edge won’t break off dramatically and crash into the water, causing a stir, a cry of pain or protest. The ocean level will rise. The loss of this glacier will be felt. When I asked how he was able not to lose hope, Léo replied, ‘if I’m not hopeful who will be?’

February 6 to February 13

January 30 to February 6

January 23 to January 29

We spoke of polar bears and whales and I pointed my phone at the view of the fjord out my window. I showed Lera a little white chocolate polar bear on an upside down plate standing in for an iceberg and we laughed. I took this photo the second time I sailed to Pyramiden. Kittiwakes are perched on scattered berglets. As the boat approached snow flurried and the massive glacier dissolved in veils of cloud: water, air and ice caught up in a dance of matter and light. This postcard from the glacier is for Lera. Like all the glaciers in Svalbard, Nordenskiöld is melting fast.

January 16 to January 23

It was the evening of my second full day in Longyearbyen. For a brief moment it looked like autumn though the icy wind suggested it was turning. I walked down to the shore again hoping to glimpse a whale or just to look out to sea. The town is much more industrial than I had expected and I wanted to turn my back on it for a while, to forget the strangeness and how far away from home I was and to feel connected by the sea. I scrambled up the steep mound that resembled a rubbish dump (it was), leaving behind the parked snowmobiles and canoes, the pallets, fuel cans and bits of scrap metal, and came upon a little cabin overlooking the fjord. There was a lot of bustling going on and several young people speaking English and looking purposeful. Sitting in her little room, Venka was keeping them busy and showing them what to do. Venka came to Svalbard many years ago and has no intention of ever leaving.

January 9 to January 16

January 2 to January 9

December 19 to December 26

December 13 to December 18

This is the view northwest from Fuglefjella – Bird Mountain. The birds had all flown South when we hiked up here, though we saw a pair of ptarmigans and a few reindeer.

We climbed up a narrow ravine and along the plateau to the edge of this cliff. It was snowing and windy, until we reached this view of a string of pink mountains floating above the sea. I fell under the same spell as everyone else, imagining Ultima Thule – the overused northern no-place, to yearn for but never reach. Tired out and with freezing fingers and noses, standing on the edge, only 1400 miles from the North Pole made it almost believable that over the horizon was a heavenly land of milk and honey.

December 5 to December 12

November 28 to December 5

October 17 to October 24

I took this photo moments after we got out of the parked bus to walk towards the abandoned town of Pyramiden. Our guide, Igor, with a rifle slung casually over his shoulder to protect us from polar bears, explained that the previous weekend he and another guide in Pyramiden had climbed up the side of the mountain to fix the words PEACE beneath the Russian words Миру Мир (Peace to the World). I asked if it was a difficult climb. He said it wasn’t very high, but the ground was very loose and they kept sliding back. They also knocked the hammer and sickle half way down the mountain by mistake. I didn’t quite know what to make of Igor’s deadpan delivery. I would find out more in the coming weeks. In the meantime, in those first minutes in Pyramiden, I felt the strange geometry of the landscape pull me into its force-field like some otherworldly Solaris-like realm. My eyes flitted about searching the horizon for polar bears, in between dipping back into a past I knew had absolutely vanished in 1991. I’d been there at the end. This was a film-set, but more stirring and alive and contradictory than any film set.

October 10 to October 17

October 3 to October 10

July 4 to July 11

June 13 to June 20

June 6 to June 13

May 2 to May 9

April 25 to May 2

April 11 to April 18

Letter from Dunnet Head: cosmic egg rolling.

I saw a huge form, rounded and shadowy, and shaped like an egg… Its outer layer consisted of an atmosphere of bright fire with a kind of dark membrane beneath it… From the outer atmosphere of fire, a wind blew storms. And from the dark membrane beneath, another membrane raged with further storms which moved out in all directions of the globe. Hildegard of Bingen, Scivias

Hildegard of Bingen, the medieval mystic and nun, had a vision of the world as a Cosmic Egg. She depicted the earth as a chaotic ball of confusion, contained within an egg-shaped universe. The four winds blow through this universe, concealing and revealing the heavenly bodies. Hildegard believed that the winds would eventually articulate a harmony with this chaotic world and the people in it, establishing calm and clarity, inside and out.

On Easter morning we painted the eggs that we had hard-boiled, then placed them in a box, and drove with our children to the nearby cliffs where the lighthouse stands, on the most northerly point of Scotland. The winds were blowing hard from all directions. The islands of Orkney were hidden by mist and the curved horizon was all sea and sky. We pushed our way through the fat and tearing gales and rolled our painted eggs at the edge of the world, through the slopes of heather, putting our hope in ritual, repetition, and the force of the winds.

April 4 to April 11

March 7 to March 14

February 21 to February 28

I was in Odesa in August 2012. You can watch a short film I made there, here on the Crown Letter. Ten and a half years later, nine years since Russia annexed Crimea, and one year since Russia invaded Ukraine, the brave city of poets and sailors has not fallen. The port is shipping Ukrainian grain to feed the world (slower than usual because of Russians holding up the process). Listening to the swerving of the trolleybus I am bumped back into that time, gliding through the city to join my friends at a sidewalk café, or pausing to watch a young gymnast practice in the park, or strolling along the sandy beach trying to stop the boys from running into the sea because it is choppy, and dirty here. Odesa’s beach isn’t safe now. I read that it has been mined.

February 7 to February 14

https://women-of-influence.co.uk/project

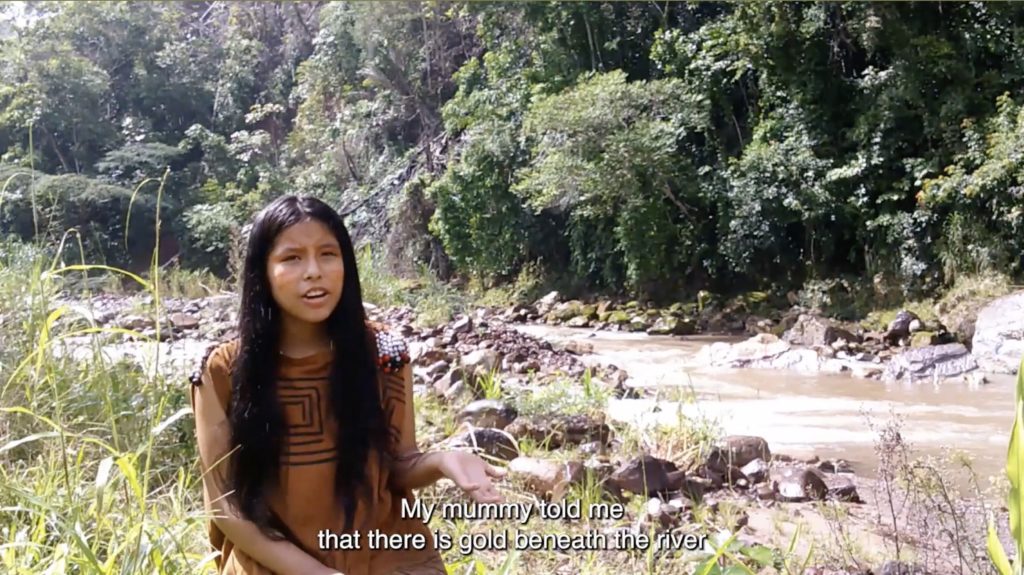

This still is from the film, The Intergenerational Struggle

for Collective Territories, (11 minutes, 2022) directed by Karen Pamela Huere Cristobal & Anyely Martínez.

“We dream of being the generation that raises our voices and are heard; we dream that our generation speaks up for our territories and that more young women join forces to understand our mission as indigenous women. Just like the Congona tree that stands firm and provides food for the cibuaco bird with its ripe fruit, so our mission will grow tall and will nourish others who would normally follow our parents and authorities. We want to be heard so that communities and organisations are informed about our rights and issues, so that they might give us space and help us to strengthen our resolve; heard so that the state recognises and acknowledges our agenda and our proposals as young people, as women who are part of a community and a people.” – Karen Pamela Huere Cristobal

I met Karen last week at a screening of her film, alongside four other films made by a group of young Indigenous women activists in the Peruvian Amazon region of Junín. The project is a collaboration between women researchers in Peru and the UK (https://women-of-influence.co.uk/project). Karen had travelled with colleagues from her community, facing extraordinary obstacles along the way because of the political upheavals in Peru today, and the remoteness of her village. They arrived just after the screening, and spoke powerfully about their determination to stand up to mining interests and a hostile government wanting to suppress their culture, and about the community’s efforts to adapt to a warming climate, by planting trees. I was invited to the screening because Karen had recorded sound for my film Treeline, in autumn 2021. The rain had been so heavy that flooding had damaged their internet connection so they couldn’t send footage. The sound however immediately conjures a buzzing, mysterious jungle, teeming with lives.

January 24 to January 31

Yesterday I walked from Covent Garden to Whitechapel through the City of London. Not as quiet as I’d expected on a Sunday, but there seem to be a lot of tourists in London at the moment and it was sunny and bright. This tree with its concrete casing stopped me in my tracks: rings the only sign it had lived, trapped inside a small fortress. My eye was then drawn upwards, up the blue metallic cylinders of Lloyds of London, ‘the World’s insurance marketplace’, as it boasts on its website.

The building was designed by Richard Rogers and opened in 1986. Five years later Lloyds nearly went under, but was saved, although many of its so-called ‘names’ (often small investors who unwittingly invested with unlimited liability) did lose everything. Insurance could be one of the ways to stop the madness of funding fossil fuel extraction. Meanwhile the ice caps are melting and the physical world literally imploding, as permafrost becomes former-frost and ice sheets slide faster and faster into the ocean. These shiny towers lean into each other – instead of trees – high up above me, reflecting themselves and the sky, completely out of touch. Of course that is the point. Anything could be going on in front of a screen, inside a steel and glass tube – I’m in front of a screen myself as I write this, looking at the picture of the steel and glass tubes. You could be insider-dealing or investing in windmills, selling mortgages or weapons, or all of those things. The little street across from here is called Saint Mary Axe, named after a medieval church that was destroyed in the 16th century. I’m glad the name has stuck although no one quite knows what it means. Whose axe? What was it used for? A name is a stubborn thing, that can keep on conjuring – haunting, stirring – even when no one remembers where it came from or who first used it.

January 17 to January 24

Today the late afternoon sky glowed, after the hail flurries, while the winter street below lay in dark shadow. The idea of heaven as a place up above must have been dreamt up on a day like this.

November 15 to November 22

It is not easy being a father, I imagine, just as it is not always easy being a daughter, or at least father to a daughter, or daughter to a father. (I’m leaving sons and mothers for another day).

I am extrapolating from my own experience of being a daughter to my father to think about fathers and fathering. My feelings for my father may not coincide at all with yours. My loss and grief at my father’s illness and death a few years ago may have no bearing on anyone else’s experience, but they might. These few, halting paragraphs represent several days of trying to find a few words to think with, or between, and for others to think beyond.

There is a shape in my life that is my father. My father’s life is part of the family architecture, even after he has gone. His passions – politics, friends, the Highlands, art and music – and the focus of his attention inevitably drew mine, and helped define where I looked and listened, even though I wandered off and sought out other things. However much we fought, and we did, it feels to me now like my frustration and rage served a purpose. It was part of working out who I was for myself and letting him know I was on the case, and he couldn’t tell me what was what or where I should go or what I should do. Even if he did. And I’m glad sometimes that he did because it’s not simple being a daughter or a father and the brief outbursts express some of these complicated feelings. Children of course help their parents work out where they’re going and what they should do, even if they (I) don’t always appreciate it. Anyway whatever the ups and downs, I love my father, and my father’s love helped make me and it is in my bones and that is what remains. As my father faded, his words fell away, until all that remained was, ‘I love you,’ until that too was said silently, with eyes and a wistful smile that lit up his face.

I asked Robin what it felt like to become a father. He couldn’t remember exactly because being a father is in his bones now, and he is very good at it.

I think that it must be hard to be a father, if you are a good one, or good enough. Messages about parenting are mixed, scrambled. There is still an immense if often unspoken social pressure to be a breadwinner, to provide financially for the family. I can imagine wanting to rebel against that expectation, even while acknowledging that providing is necessary; especially if you also feel the demands and hopefully the desire to share in domestic responsibilities of care. But the language of fathering – not ‘the name of the father’ but the intimate care and love of a father – isn’t as developed as it is for mothering. Mothers too need to provide as well as occupy a mothering role that is simplistically thought of as natural, obvious, profound. The responsibilities and pressures aren’t new, but the forms they take are always evolving. Both roles can be confining but don’t have to be, if they’re shared and improvised with (and not just by parents).

Here is a bouquet of wildflowers for you, for your father. They smell of the sea, of heather, of bee-seducing nectar, and a little bit of sheep.

September 20 to September 27

September 6 to September 13

July 19 to July 26

It is almost always summer

In my dreams and in my memories it is almost always summer in Ukraine. Late July, August. Hot with a warm breeze, and maybe cool late at night when we walk by the river after dark.

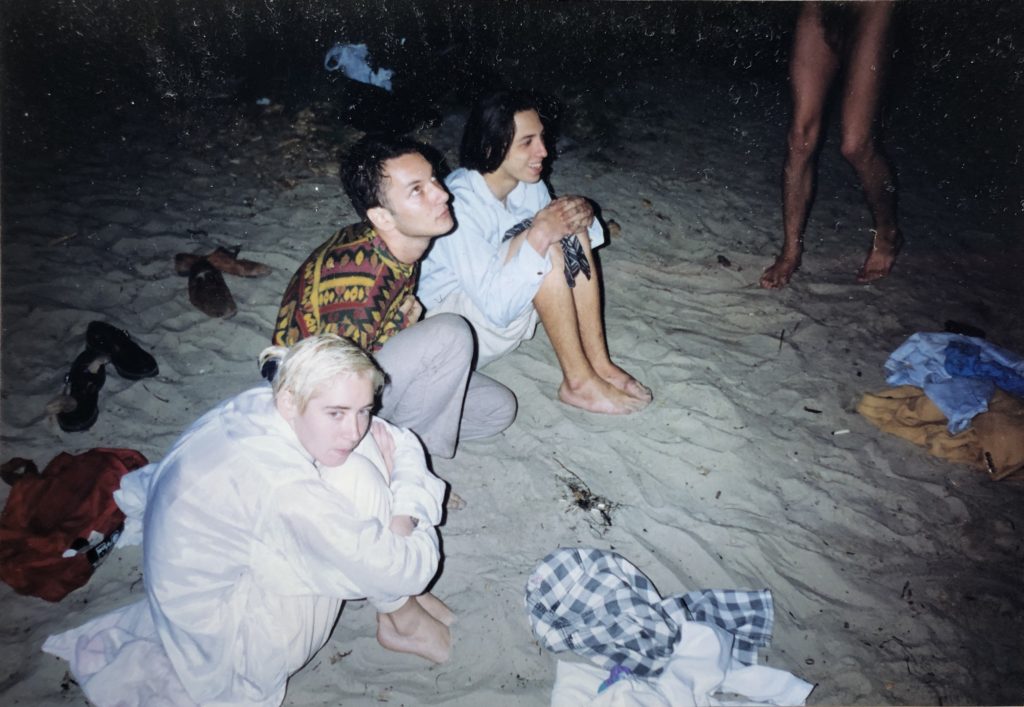

It’s a warm evening, after a bright, hot day in Kiev. I’m sitting on a narrow old balcony, high above the street, in the Kommuna. Lera gently holds Hans to her face and kisses his nose. The sleek, gold-brown rat wriggles, and sniffs. He’s a friendly soul and I manage to stroke him, suppressing my impulse to flinch. I’m ravenous from carving stone all day in the heat. Lera knows and without really asking hands me a little bowl of something delicious (as she does most days). It might be tvorog with smetana and honey, or some vegetables and rice. I’ve brought a bottle of wine.

We’re laughing from the heat and joy: of being artists, of being young and beautiful running free in this city reborn. We’ve run down the steps to the water’s edge. Later, we’re on a wooded island in the Dnipro not far from the city centre. A small cardboard box is laid gently on the dusty path. Sasha opens it carefully and coaxes out the scared little inhabitant. In the quiet gloom, we’ve fallen silent and watch as the tiny hedgehog unfurls itself and steps out gingerly. It shuffles as quickly as it can into the bushes. Several of the boys have taken their clothes off to swim, and the girls join in too. It’s so hot. We whoop and laugh some more. I’m so tired as we climb back up the steps.

I’m sitting in a big studio, in the Paris Commune (named after the street it’s on, which is no longer the Paris Commune but was handed back to a forgotten Mikhailov). Paintings line the walls, maybe to be photographed or just to show to friends. We gather every day in one or other space, to drink a little cheap white wine, or fresh Kvass that I buy on my way from the carving site, or sometimes Cognac or beer, but always tea, some smoke papyrossy filled with Odesan weed, and nibble on nuts or corn snacks.

My right arm is very strong now, stronger than it will ever be again. I can see my biceps standing out. I have been hitting a mallet for eight hours every day against a metre-square block of limestone. Dima – nick-named Ligeros – says, ‘if it were me, I’d carve an iron out of the rock.’ I can’t do such straight lines, and it’s hard to hold onto a joke or a concept as chips fly, and my eyes are blinded by dust and sweat, after eight hours of banging a mallet. I imagine his iron, for longer than he does I’m sure. I’m not sure what I’m doing, but I’m in the swing of it enjoying being strong and keeping going in the heat. I can’t give up now. This will be my first and last stone carving. I am caught up in a performance that has been going for years, from another era, an unexpected but diligent addition to the bearded cast of sculptors. This era will soon be over.

Ligeros invites me to join the Cloud Commission – to watch and learn and share our pleasure at the overlooked beauty of clouds. We walk about with our heads thrown back looking at the sky, and he hands out photocopies of pictures of clouds from books, and his manifesto. After a solemn ritual I am officially welcomed into the secret society of Clouds.

We go on long walks through dusty summer parks to secret overgrown vestiges of Soviet heroic spaces, that I can no longer picture exactly but still remember the light and heat and smell, the broken glass, and shadows.

And then there was the building with the arch where you enter from the sidewalk and suddenly find you have to crouch down to reach the courtyard: an Alice moment realised in stone.

That summer was long ago, a year after Ukrainian independence. I’ve turned the fragments over and over in my mind till I no longer know what shape they are. Twenty years on, another summer is also receding in the wistful glow of holidays and childhoods remembered. Another ten years, and here I am far away from Kiev, Odesa, Crimea, missing friends: some who died, some who remained, and some who are now stranded or staying put and helping out, fighting or just trying to keep on living. I hope and pray that summer will return to Ukraine, that the Dnipro and the Black Sea will be safe to swim in and young and old will again strip off and take the plunge after rescuing a hedgehog.

June 28 to July 5

June 22 to June 28

June 7 to June 14

May 24 to May 31

These two saplings sprouted from acorns I collected in the park last year, or the year before. They’ll need more room soon, so I’ll plant them out together. They grow slowly and could live for four hundred years or more. These are common oak – English oak, Pedunculate, Quercus Robur. In England however, many of the oak groves were cut down to build ships to fight Napoleon and have never fully recovered. The oak is also the most common tree in Ukraine, Dub. The D is important – Dodona was an ancient Greek city, loved by Zeus, appointed to be his oracle, where doves lived in the hollow of an oak. A place for prophecies and prophetesses.

Oaks grew in the world and minds of the Druids, who worshipped in oak-groves. Ireland is still covered with oaky names if not as many trees – Doire, Derrybawn (whiteoak), and Derry-Londonderry was once Derry Calgagh, the oakwood of a fierce warrior. Kildare grew from ‘Cill-dara’, the Church of the Oak, where St. Brigid founded her abbey. Her namesake was the goddess daughter of the Sun-God Dagda, for whom the oak was sacred.

Further north, the oak spread its roots as the mighty tree of the Norse god Thor. It is holy to Pagan Celts, and later, Christian ones like Saint Columba. Holy oaks are protectors, strong defenders of the righteous. They can survive lightning strikes and grow with renewed vigour. Oaks can be semi-human, like the Green Man who dies and comes back to life each year. And they can be goddesses, Dryads. The oak can lift up girls and hide them from unwanted suitors.

Duir in Sanscrit is a door, through to wisdom, or at least a foretelling of the future. Perhaps this is the root of Druidry or one of its entanglements. Dorja is still a door in Bengali. Although oaks do not grow in Bengal, the roots of the oak tree and its acorns can spread far.

In Ukraine, the Dub grows tall and its branches spread wide, invoked in folktale and song. The oak is mighty and gentle: it feeds with its acorns, cures ailments with its bark, shelters nests in its canopy, gives wood to build houses and ships and churches and deserves to be holy again, to be protected in order to protect.

[thank you to Druidry.org and other virtual places, and to Robin for all the oak lore]

April 26 to May 3

The following is a letter I wrote to the curator I was working with in 2013.

‘I have decided on a title for the exhibition. The title is ‘The faces they have vanished’. It is inspired by a quote from a film maker in 1937, about the faces that appear in films vanishing, and reappearing, only to vanish again, so evoking the magic of the moving image, and also its spectral quality. For me ‘they have vanished’ suggests the faces of poets and artists, that we know from photographs – who appear so distant in the photographs but whose writings are so immediate and contemporary. It suggests the artists and poets, and many other unknown people, who were ‘disappeared’ during the Soviet period (Mandelshtam et al). ‘The faces’ is somehow impersonal, and yet a face is personal, unique. There are many faces in my film, known and unknown, remembered and sought, and they do vanish – glimpsed briefly, sometimes filmed, and then passing on into their own lives, away from the gaze of the camera. It also points to the disappeared of Crimea through the centuries. Everyone seems to have crossed Crimea: the Greeks, the Romans, the Genoese, the Turks, the Khazars, the British (in the Crimea War), the Russians and Ukrainians. The most recent and genocidal disappearance of a people however is the forced exile of the Crimean Tatars in 1944. They were accused of collaborating with the Nazi occupiers and sent to reservations in the deserts of Uzbekistan, far away from any other inhabitants.’

Less than a year later, Crimea was seized by Russia. Less than a decade later, many more faces are vanishing.

The term ‘observatory’ hides a multitude of uses more or less benign. This one is nestled in the hills above Feodosia in Crimea.

April 12 to April 19

The railway line runs right through the centre of the town, making it easy for holidaymakers to arrive and depart. This is a hot summer day in 2012, in this sleepy town in Crimea. In 1944, the Crimean Tatars were rounded up, accused of collaborating with the German Nazi Occupiers, and forced into exile, in what is known as the Surgun (meaning Exile). They were sent to camps in the Soviet Republic of Uzbekistan by Stalin. Some of them would have left from here; half of them never arrived. It was years later before Crimean Tatars were exonerated and later still before they were allowed to return to live in Crimea, only to find their homes and villages destroyed and the Tatar names erased. In 2012, the Tatar Medjlis, its representative body, was thriving, able to negotiate with the Ukrainian government to assure the rights of Tatars and preserve their heritage and culture. We met with historians in Bakhchysarai where the Tatar archaeological site was being excavated and preserved. Robin made a radio broadcast about it and wrote this article. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-19815852

In 2016, the Medjlis was banned by the Russian government.

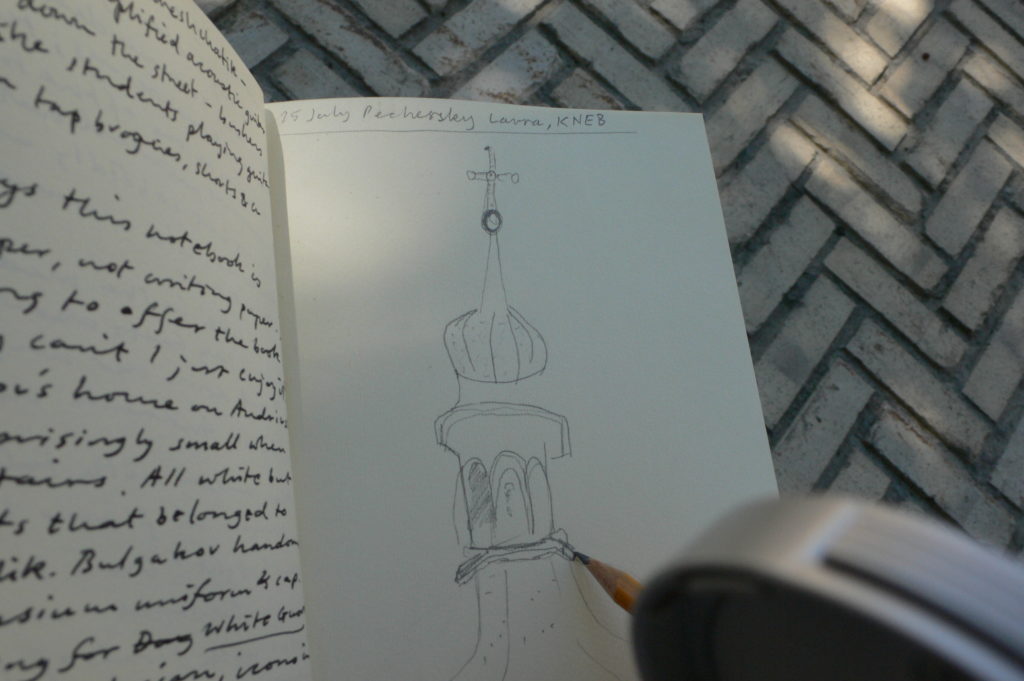

Another memory that I have no photographs of, is a view from a train window. It was Orthodox Holy week, in 1992, and I was on a train from Kiev to Moscow. We passed a church and outside it was a procession. I remember blossom, a sunlit crowd of women wearing embroidery and lace, and a cross being carried by a priest, and bells. It is almost a hallucination now, just the movement and glow of the day remaining as an afterimage. Later that day, my companions on the train, strangers all, shared their lunch and an Easter cake with me, paskha (kulich in Russian). If you’d like to bake one, here is a recipe. https://ukrainian-recipes.com/traditional-kulich-old-easter-bread-recipe.html It is sweet and delicious, made with lots of eggs and milk and sometimes curds, raisins, nuts… everyone has their own variant. This year Holy week in the Julian calendar, which the Ukrainian Orthodox church follows, falls a week after the Catholic and Protestant Holy week. Here is a photograph of the Pechersk Lavra Kyiv, that I took that same summer of 2012.

My heart is with the people of Ukraine, waiting in railway stations or already in exile, fleeing war or staying put and waiting it out, and of course, the many who are fighting for their lives and their country.

March 29 to April 5

March 22 to March 29

March 15 to March 22

Koktebel’, Crimea, 2012

We walked up the hill to Maximilian Voloshin’s grave above Koktebel. A great walk to the view – where Max V would light a fire on his way home from the gymnasium in Theodosia to Koktebel and his mother would see it and prepare for his arrival. People bring pebbles from the beach to lay on his tombstone; sometimes they write on them or leave money. Then we walked back down, tasting caperberries growing in the long grass. We walked to Dead Bay next to Quiet Bay. We ran into the family we’d met on the walk up, at the beach. N and A and the twin boys. We swam in the sun and moonlight, spread the soft, black, sulfuric, magic mud all over our bodies and floated in the warm still water. We then all squeezed in to the car to drive home for tea, champagne and melon. The boys played chess and understood each other fine.

We spent several happy days together with the family we met on the walk. They rescued us from a place with twenty cats and no hot water. We stayed with them in Theodosia, and the boys played chess and ran around shouting together. Now please come and stay with us!

March 8 to March 15

Theodosia means gift of God. The city is ancient, founded by Greeks in the 6th Century BC. Crimea has always been desirable, and was settled by Khazars, Tatars, Greeks, Genoese, Russians and Ukrainians, and many others too. Theodosia (or Feodosia) is the port from which the Black Death was carried to the rest of Europe by sailors. I took this photograph on a hot summer’s evening in Quarantine, the oldest surviving neighbourhood of the Genoese city.

Looking at this picture now I wonder what happened to the boy who was reaching to the sky, swinging and balancing, beautifully poised in his element. The sky was so blue it felt like a substance you drown in. A little over a year after I took the picture Crimea was seized almost bloodlessly by Russia, and annexed. This was the beginning of the war that was kept at arms-length by the rest of the world, hoping it would just go away. The Russian invasion of Ukraine twelve days ago has shocked the world, although those who have lived through and been traumatised by the eight years of fighting in the Russian occupied territories, in Donetsk and Luhansk, were perhaps not surprised.

The boy in the photograph is now old enough to be fighting and could be on either side.

March 1 to March 8

I filmed this in Odessa in 2012. The original work was shown in a wooden structure inspired by Gustav Kliutsis’s drawings. The title comes from Battleship Potemkin by Sergei Eisenstein.

Odessa is a beautiful city, built by Italians for Catherine the Great on the Black Sea. It is a major seaport and formerly headquarters of the Imperial Russian fleet. It is famous for its Jewish heritage, its humour, its writers and its counterpart on New York City’s Brighton Beach.

Sergei Eisenstein’s film The Battleship Potemkin celebrates a famous mutiny in 1905, a precursor to the Russian Revolution of 1917, showing the solidarity of the Odessan citizens with the brave sailors rising up against their oppressors. This film has one of the most famous scenes in cinema, of Imperial Cossack guards shooting the onlookers who are cheering the sailors of the Potemkin. A pram rolls out of control down the steps, close-ups of horrified faces, broken glasses, and the cries of mercy of a distraught mother carrying her dead child up the steps to challenge the unprovoked aggressors. A modern Pieta. The scene was shot in Odessa, on the Potemkin Steps – which were renamed after the film. The massacre of course never actually happened. But history has taken over. The Russian Revolution did happen.

And now, once again and in reality, Odessa is under fire, this time from the Russian army and navy. Odessans will triumph. Peace in Ukraine. МИР НА УКРАÏНИ

February 8 to February 15

The choir meets once or twice a week to sing traditional folk songs from Pinega. They gather in each others’ homes to rehearse and enjoy food and company. Like sisters, like the Crown sisters, they keep each other going and make art together. Some of them are in fact cousins from the same village. They have been on tour to Norway and elsewhere but mostly sing in Archangel. One of them had just got married and invited me to the feast.

I look forward to feasting again (and maybe even singing) with my Crown sisters in the spring.

Na zdorovye!

January 25 to February 1

I visited the uninhabited island of Stroma with an ornithologist and a marine biologist from the university of the Highlands and Islands in Thurso, in 2013. Stroma was abandoned in 1958, and is now owned by a family that used to live on the island who keep sheep and a couple of holiday homes. While the scientists watched guillemots fishing and sent a remotely operated vehicle to the bottom of the coastal waters to film the sea floor, I walked north across the island. They warned me to watch my step. As you walk along the grass the ground suddenly falls away. I dropped down and leaned over the cliff-edge as if to watch the fulmars roosting on the ledges, but really to hug the solid earth underneath me as the sudden shift in scale made me dizzy.

The Gloop is a quite shocking piece of geology. It is a huge hole in the ground that is invisible until you get quite close. The sea rushes into it through a narrow tunnel, and seals, and probably the occasional orca, swim at the bottom. I watched grey seals playing that day I and listened as their barking was amplified by the cliffs. I used a very wide-angled lens to try to take it all in. The sea has almost vanished in the over-exposed sky except for a pale but large vessel floating in the distance.

In the past weeks I’ve been looking at photographs of open cast mines in the Arctic and what look like huge sink holes caused by collapsing permafrost with methane bubbling to the surface, and then recently images of the underwater volcano near the Tonga archipelago that caused a devastating Tsunami to engulf the islands. I don’t know how the Gloop formed, but it feels like a dramatic event made the ground collapse, or a giant missile (a meteorite or asteroid) hit it and the rock just crumpled. Here the sea is underneath as well as all around the island, and it feels like it is only a matter of time before the dinghy capsizes. How terrifying it must be to live with rising sea-levels and water pouring over the edges of your home and knowing the ground isn’t safe beneath your feet.

January 18 to January 25

This winter among the trees of sub-arctic Russia I find light and heat become elusive, granular substances that take on indistinct but alluring personalities. The day’s light scatters quickly if you aren’t alert, and even if you are it is still always fading, dispersing like sugar in tea. The rainbow colours of afterglow on snow dissolve into the night and before they disappear they melt the edges of things, blur bodies and sharpen windows and other angles. In my longing I find delight in the glitter of vestiges of sunlight catching the crystals of snow, or the lazy, sleepy blue that holds on till I find myself tramping through shadows. I notice suddenly that my ears are tuning in to the loud crunch of my heavy lumps of cold feet and that the sound is all that is guiding me.

Heat is all inside, held close, fiercely protected by doors and down, wool and fur, to stop it from escaping. The stoves are always hungry for more wood, and our bodies for more food to keep us moving, to keep warm and warm the air we breathe. As soon as we go indoors, removing layers, the burning-wood heat envelops us and our bodies let down their guard and we need to lie down for a nap.

January 11 to January 18

I have been following the news in Kazakhstan, of uprisings and violent retaliation, the suppression of protests and the threat – or promise – of troops from neighbouring countries. I can imagine how frightening and worrying it must be to be holed up in one’s home wondering what is going to happen.

I am posting this picture as a sort of postcard – or really a love letter to the beautiful Apple City of the Tien Shan mountains with its treelined streets and months of sunshine. I took it in the famous candy store the summer I taught film at the ‘School of Artistic Gesture’ in Almaty. It was a wonderful week with incredibly talented and committed young artists who are the present and future of Kazakh art.

I first visited Almaty in April 2006 with Anna Harding and Kathy Rae Huffman, at the invitation of the British Council, and I made a film about eagle hunters – Valley of Castles. Many visits and several films followed, and many friendships. My next film, Capital, addressed a ‘Prince’ who has built himself a new capital city that reflects images of himself in fountains and mirrors, ignoring the palimpsest of cities that exist concurrently beneath the shiny capital. The capital of Kazakhstan where I shot my film was renamed Nur-Sultan a couple of years ago. Now at last the mirrors are being shattered.

I am thinking of Kazakhstan and hope that 2022 brings freedom, joy, and good health, and that peace and hope lie ahead.

P.S. You can watch Capital here https://lux.org.uk/work/capital.

January 4 to January 11

December 14 to January 4

Ruth Maclennan, Albina Mokhryakova, Sofia Skidan – WAVES OF CARE, a collective art work for TRIGGER

There are many rituals surrounding the Russian banya. As I was told it is just the place to bathe, in villages that used to have no running water. But it is also a place and time to take care of yourself and others. Beating each other with moistened venniki, often bunches of birch leaves, makes your skin tingle and increases the heat. The wooden house in the village I stayed in had two banyas (and no running water). There was a white banya (po belomu) where the wood-stove has a chimney, and an old-fashioned black banya (po chornomu) without a chimney where the smoke settles in the room and the soot cleans your skin. The banya is also a place for foretelling the future. Sergei Kulikov, a historian I met recently, told me that the banya was traditionally seen as a profane, unclean place because of its pre-Christian, pagan associations with fortune-telling. I made this film together with the artists Albina Mokhryakova and Sofia Skidan.

December 7 to December 14

4 o’clock, Vershinino – ERASE THE BORDERS, a collective artwork for Bienal Sur (Argentina)

The light is fading, but not evenly. Shadows deepen and edges blur, but some birch trees snatch the last gleam and hold onto it, as if lit from within. The sun is a ghost now, and night is a place that quickly forgets. Like the birches I am desperate to soak up the last of the light, tramping through deep snow, barely able to see through the viewfinder, which steams up as I try to focus on lines that refuse to be sharp. I’m drawn to shadows, where fairytale beasts might lurk and come out and speak if I stay still.

This is Kenozero, a large national park in the Arkhangelsk region of Russia, which is the size of France.

November 23 to November 30

November 16 to November 23

ERASE THE BORDERS a collective art work for Bienal Sur 2021 (Uruguay)

I look out at this mountain every day as soon as I wake up and keep checking on it as if it were the barometer that could suggest what the day was good for. I can’t tell how far away it is, or how massive, or how much sea separates us. I feel it solidly there even when it disappears during the long Arctic night, which is most of the time. I have approached my mound from low on the ground at sea-level first thing when the raw day tears through the wispy listless fog and night and drags me outside to touch it, to believe in it. I’ve climbed up the mountain opposite, to get a handle on it, to see the lie of the land, and see the house I’m sleeping in and looking out from. I’ve walked along the beach and cycled along the road to see it from other vantage points and to get past it and look at other mountains. One evening I saw at last – or did I? – a feint veil of aurora waving at the mountain’s void from the left, due north, unaware, unspectacular, unphotographable.

The sheep milling around the muddy, seaweedy shore, enlivened by bales of boozy silage, have now been moved, probably indoors, and the fences have been taken down for the winter.

This was Sámi land, and before that unnamed people lived here, or visited at least, and drew (in red pigment) stick people dancing, in a cave out of reach of almost everyone, inside the farthest island, beyond the steepest narrowest ridge, next to the still terrifying, unpredictable Maelstrom. Was the red pigment made from Rowan berries? I thought this today glancing at the last bloody smear across the brown before they all drop. Not like the other day, when up the mountain the berries sparkled on their bare branches like fairy lights, flirting with the birds.

We talked and laughed with you Ivana as you showed us the MAPI Museum of Indigenous and Pre-Columbian art where The Crown Letter scrolls of the weeks have been hung. I drank in the sunshine through the windows opening onto the bright blue sky and southern sea, with a view of the Customs House in Montevideo. It felt very planetary, to be sitting in the dark on my Arctic island peering at a little screen that beamed me up to a satellite in space and down and around the world to you in Uruguay, and to Manuela and Natacha in Paris. I wanted to send you something from this part of the planet, something to connect Sápmi with the lands and people the MAPI museum is devoted to. Sápmi is the name for Sámi country, that stretches across northern Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia. I send you pictures of this mountain that seems to stay put, but is actually rising, while everything around it moves.

November 9 to November 16

ERASE THE BORDERS a collective art work for Bienal Sur 2021 (Argentina)

This photo is taken in Kvalnes, a village in the Lofoten islands. At this time of year a Sami filmmaker friend of mine said the landscape closes up and the body’s borders blur.

October 26 to November 2

ERASE THE BORDERS a collective art work for Bienal Sur 2021 (Argentina)

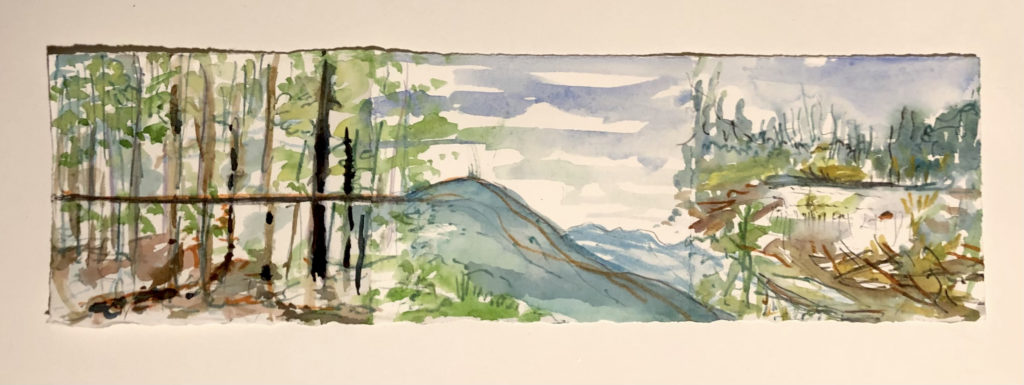

I have been editing together clips sent to me from around the world to make my film Treeline. The unfolding film does in a way erase borders as I stitch together an endless forest landscape, with natural and man-made, planted, destroyed, temporary and evolving treelines. This drawing is of tree lines I am very attached to from a place that inspired the film – a pipeline carrying maple sap, a view above treeline, and a beaver dam changing the flow of the Moose River. The drawing is for C on her birthday.

October 19 to October 26

ERASE THE BORDERS a collective art work for Bienal Sur 2021 (Argentina)

October 5 to October 12

ERASE THE BORDERS a collective art work for Bienal Sur 2021 (Argentina)

Propagation

This is like the birthing centre or maternity ward at Bedgebury Pinetum in Kent, England. Scientists have collected seeds of trees from all over the world to propagate and preserve the different species’ DNA in living trees. Conifers are the most endangered trees, partly because they are the oldest, but also because they are threatened by climate change and human intervention. Bedgebury is like a tree zoo, or perhaps more like a benign Jurassic park where trees are planted and cared for and rub shoulders with other trees they would never encounter in the wild. Some are severely endangered and barely exist in the wild at all. Some, like the giant sequoias in California, are being destroyed by fire. Their living offspring from seeds gathered in 2007 are now 10 metres high. The forest is an uncanny but flourishing microcosm, a polyglottal palimpsest of stories of colonial conquest, collecting mania, botanical experiment, garden design, forest management, conservation and collaboration that keeps on growing. https://www.forestryengland.uk/bedgebury

September 28 to October 5

Tree Cover

ERASE THE BORDERS a collective art work for Bienal Sur 2021 (Argentina)

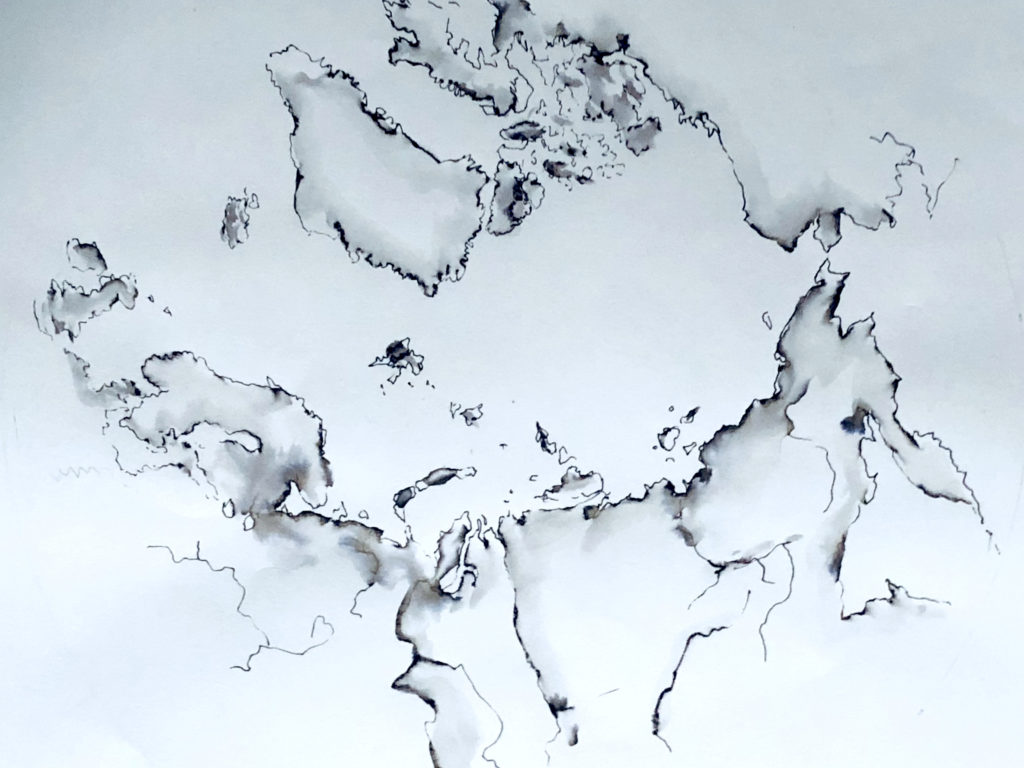

The boundaries here represent forest cleared to grow crops of soya, palm oil… The fields have borders, the forest – a rich green canopy – does not. Many areas of Amazon rainforest are legally – but not always actually – protected indigenous lands. Fires are being set, or allowed to spread, to clear forest to plant fields of soy. The political borders of indigenous lands are being erased by fire and capital. The boundaries were brought in to parcel up the forest and impose a way of seeing land and place that is not shared by those who live there. Borders are made to keep people in, and out, but don’t keep out much else without a lot of work. Borders are strange and unnatural and depend on a deliberate blindness – turning a blind eye to what they do – to be recognized. Trees, birds, fish, insects, fungi travel thousands of miles and get called ‘native’ or ‘invasive’ species – though they don’t know it.

This painted map is based on a photograph posted by Global Forest Watch. https://www.globalforestwatch.org/

September 21 to September 28

I have received hundreds of video and sound clips of trees and forests from around the world. I am touched and grateful that so many people have been inspired to join in this collective project. Looking through some of the clips, I wanted to touch the trees and smell the pine needles, the banana palms, the cypress trees – to smell smells I’ve never encountered before because I’ve never been in these forests. I stepped outside for some air and sky and walked to the little park near my studio. This is where I filmed the first horizon for the Crown Letter that gave me the idea of asking people to send me their horizons. The leaves are beginning to fall but it’s not full on autumn yet, though I found some irresistibly shiny conkers which I’ve brought back.

And now I have just painted these treelines from some of the clips that have been sent to me. I wanted to make something that I could touch, that was wet and alive like the trees and ponds were when they were filmed.

I am going to cut these into postcards and send them to Adriana in Argentina so that she can take them to the Bienal Sur and arrange them in any order she likes.

September 14 to September 21

Evening Primrose seeds are used to make evening primrose oil. I’ve often been told it helps women’s health especially easing the pain or discomfort associated with hormonal changes. I’ve never found it effective, but always felt it might be some shortcoming on my part that meant I was insensitive to its benefits. But I was drawn to this lone flower like a bee or butterfly imbibing its lemony glow. Evening primrose was introduced to England in the 1600s and is now naturalized, a wildflower that grows on verges and along old railway lines. This is on the edge of what was once a steam railway line, and has been kept as a cycle and bridle path.

August 31 to September 7

August 24 to August 31

Skumi is the Old Norse for dusk. This is the northernmost tip of Britain, north of John O’Groats, close to Scandinavia. Caithness has many Norse names: Thurso (Thor’s river), Murkle (dark hill), Scrabster, Thrumster, Lybster… I took a picture of this view in January at 3 in the afternoon, the winter skumi. Then the loch was frozen and the wildfowl were wintering further south.

July 27 to August 3

June 29 to July 6

June 22 to June 29

I would love to be here, above tree line. I dream of this landscape. It is better than dreams of flying, because I have been here before and I can smell it and feel the breeze. I am scooped up in the blue haze, looking out at the endless shadowy waves, searching for familiar peaks but happy to let the sweep wash over me. I look out from the high ground, thousands of feet above sea-level, brought there miraculously this time, not under my own steam having come from somewhere else in the dream, not through the woods. My feet and hands remember the rocks from scrambling over them, or leaping from rock to rock along an almost imperceptible trail. The cairn in the photograph is designed to keep hikers on the path, to protect the fragile alpine environment. I was on my way upward when I took this photograph, turning to look back at the last of the dwarf trees, and to have a breather no doubt before the last push up the ridge to the top for lunch.

This photograph is probably twenty five years old. The trees won’t have grown much if at all because of the altitude. It feels very fresh to me, despite the yellowish tinge. I think because I long to be here.

I am making a new film, Treeline. The tree lines of the film could be like this one – I had hoped to film this one myself, but I hope my family will film it for me instead. Like my Horizon films for the Crown Letter, Treeline will be made up of footage people send me.

This is an open invitation to all readers and recipients of the Crown Letter, and your friends, to send me your tree lines, wherever you and they may be, whatever tree line it is that you follow, or draw, or step across or under. You might film the jungle canopy, or the avenue of an urban forest, or the edge before forest becomes tundra, or the lines that interrupt a forest, a cutting, a road or river. I will immerse myself in your woods for a time, and string together treelines to tell stories of forests and their inhabitants from across the planet.

To contribute, please visit:

https://www.forestryengland.uk/treeline

June 8 to June 15

May 25 to June 1

Marigolds and Basil

This little stone Tulsi (basil) shrine used to stand in a beautiful garden on the shore of the Paglachandi lake in West Bengal. Tulsi is a goddess. The shrine was washed away in a flood.

Marigolds suggest sun and warmth. I photographed these in a little front garden near where I live.

Wishing the protection of goddesses and the joy of marigolds to our Crown sisters in India.

May 18 to May 25

May 4 to May 11

May Day

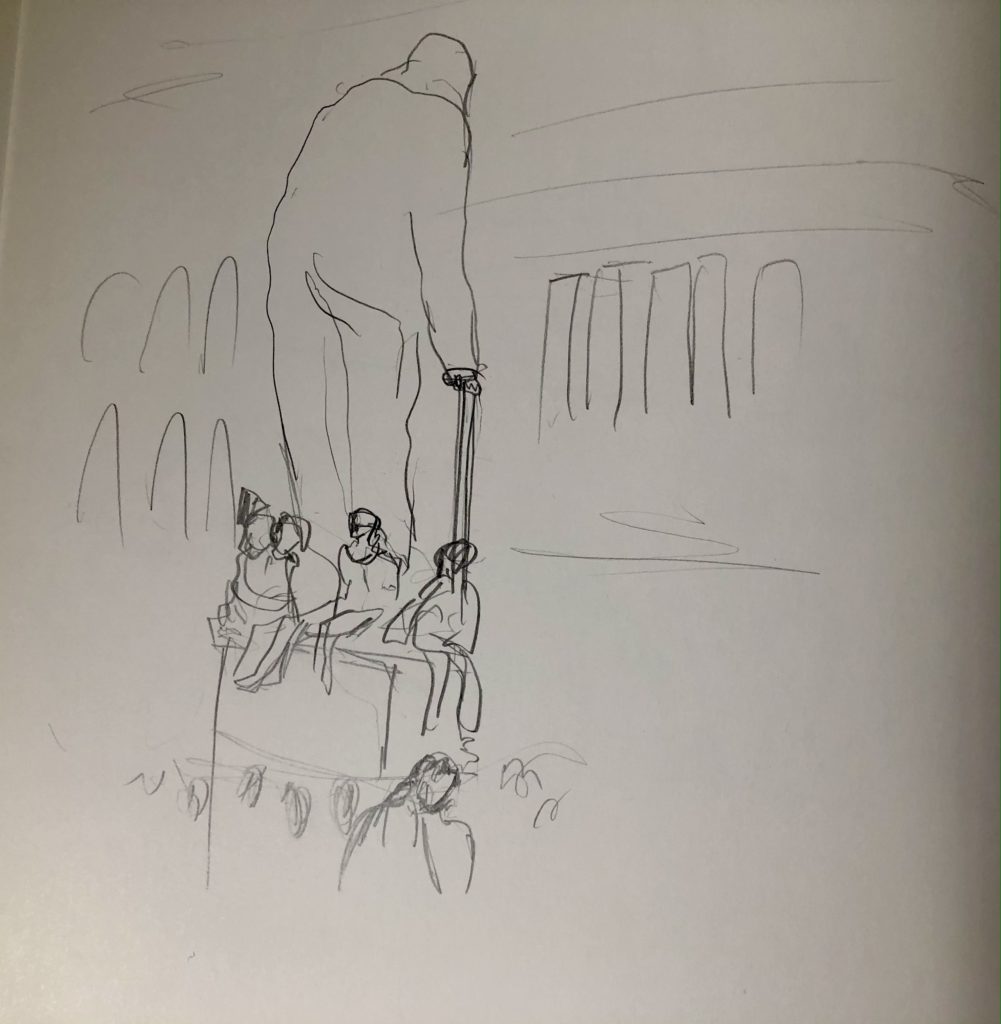

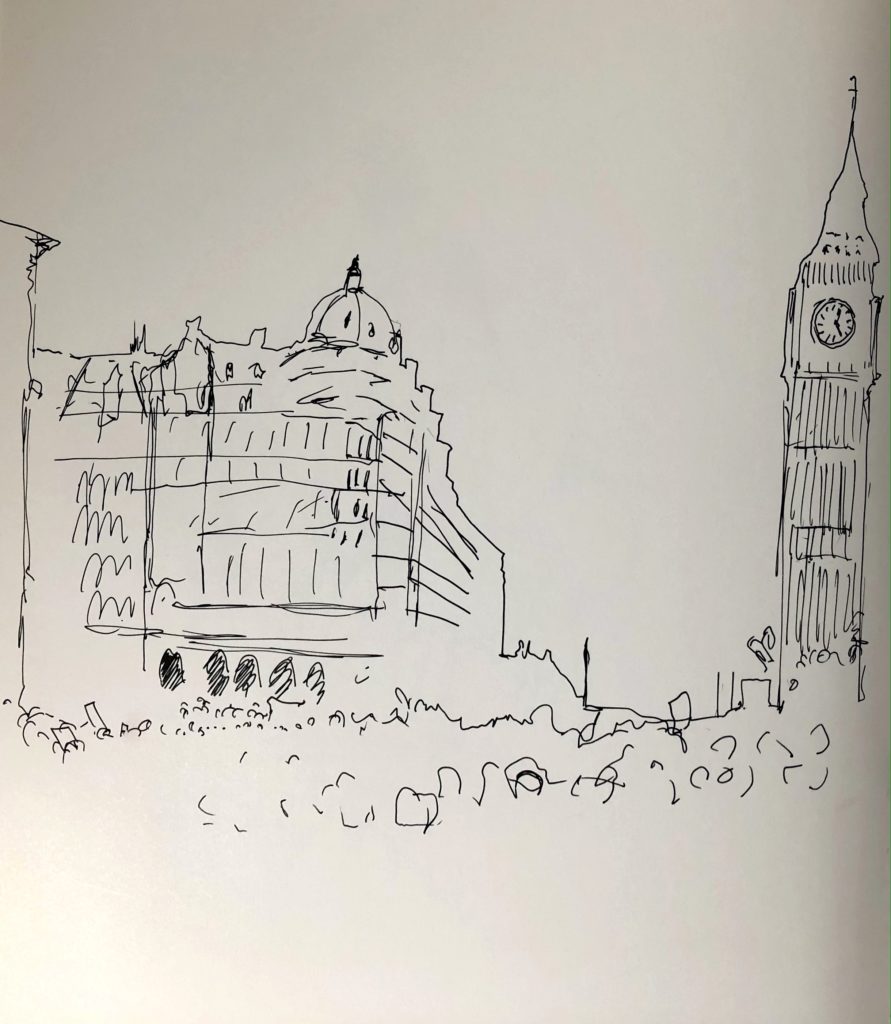

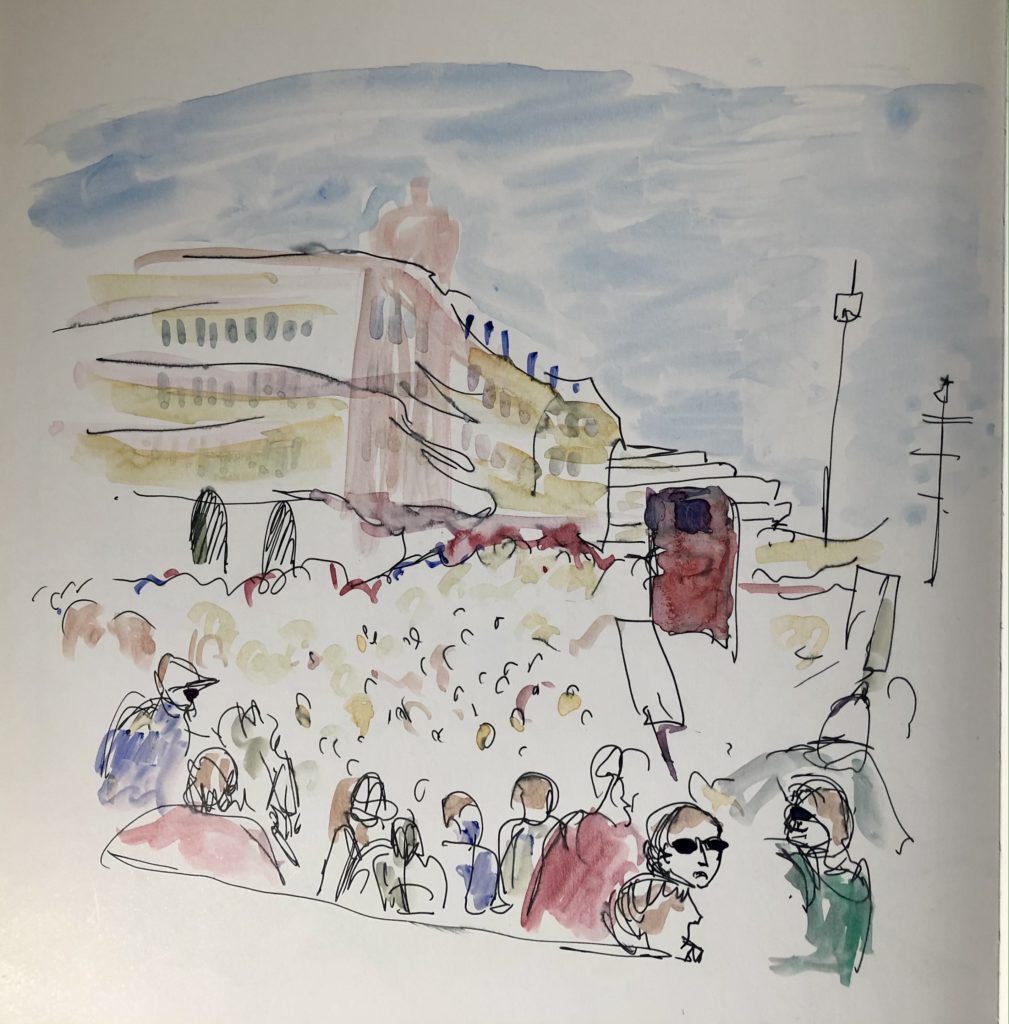

It was a warm, sunny day – perfect for climbing trees, having a picnic and marching. We did climb trees, and statues, and sat swinging our legs next to Winston Churchill’s sturdy torso; there was lots of singing and dancing, and we watched while some of us planted seeds in Parliament Square. Apparently there was a very good crop of hemp later that summer.

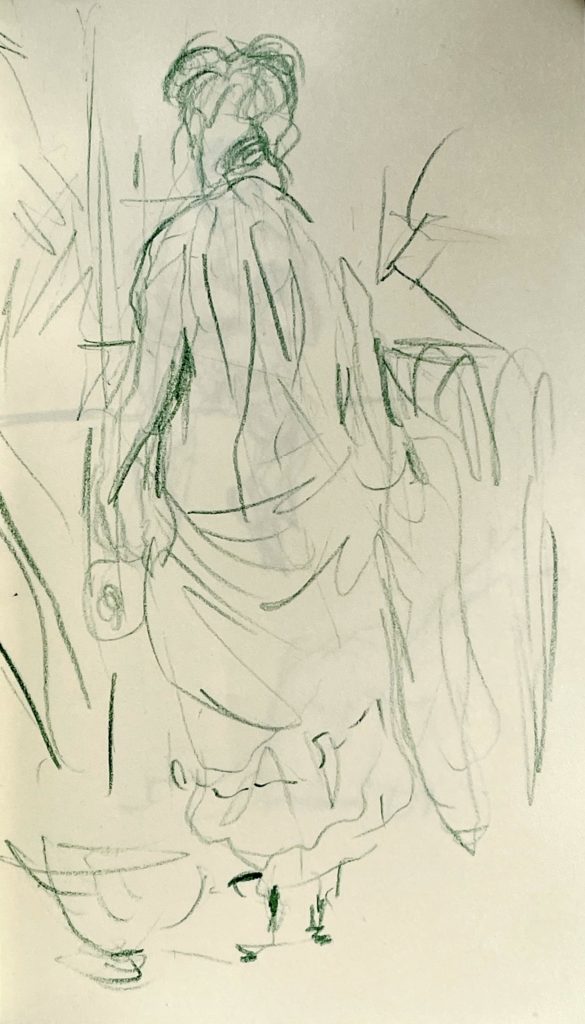

These drawings are from a May Day protest many years ago. It started as a Reclaim the Streets action, with guerilla gardening to model a different a way of living in the city, challenging the corporate sell-off of public space, and calling for action on climate change. We were exercising our right to protest, to call the government of the time to account, to use our bodies collectively to speak to power. I have been in this square many times exercising this right, before and since. Twenty one years later, this May Day, there were protests in London and all over the UK and elsewhere in the world. In the UK, this time the protests were to defend the right to protest at all, as the government is pushing a new bill that would give increased powers to the police to arrest protesters and prevent dissent – aimed at Black Lives Matter and Extinction Rebellion. So, #Kill the Bill! Elsewhere, individuals glued themselves to bridges in Extinction Rebellion’s Covid-sensitive Protest of One to address the climate emergency. Looking at my old drawings I feel nostalgic for the jostling, exuberant, joyful crowds, for large gatherings without fear of infection, or arrest. Putting your body on the line is currently riskier than ever. My thoughts right now are with Crown sisters and their families and friends in India and Argentina.

April 28 to May 4

April 21 to April 28

A Crown Garden

A year on.

‘Maybe it’s the quality of the experience of/with art that will be important, not the object. What has happened to looking at art? The context is everything, the chatter is still there, but doesn’t sound the same.’ (April 2020)

The letters and conversations have helped give the weeks a shape, if not the hours, or days or months, and certainly couldn’t be expected to shape a whole year. ‘The Crown Letter has been a lifeline.’ Not quite an overstatement. We cast lines, threads of conversation and other matter, a few notes of bird and other song, many words, leaves, streets, stones and shadows. The letters are for each other, often, or reaching for others, or for the world glimpsed through the haze. Or perhaps a letter is sometimes a gift or a kiss to ourselves in a future too hard to contemplate as we rock from fear, or grief to hope and back, from one side of the room to another, or roll up and down the stairs, the hills, the streets.

I’m not sure I can bear to look back at the year this minute. Birthdays bring one up against hard time, dates, and memorials. There’s so much going on just now, unresolved or still to reckon with. I’ll let the thoughts come unbid, worked out in my sleep or other drifting off time. Instead, these spring flowers herald new life in the garden that has fed my family with tomatoes, apples, quinces, chard, sage, rosemary, chives and mint, and cheered me throughout the year.

Instead of a cake, here is a birthday garden for the Crown Letter.

April 13 to April 20

Horizon (thirteenth lap)

April 6 to April 13

March 30 to April 6

March 23 to March 30

March 16 to March 23

March 2 to March 9

‘Sardines and moonlight…If you love me, let me know. Tell my heart which way to go…’

February 23 to March 2

February 16 to February 23

February 9 to February 16

February 2 to February 9

January 26 to February 2

For All That

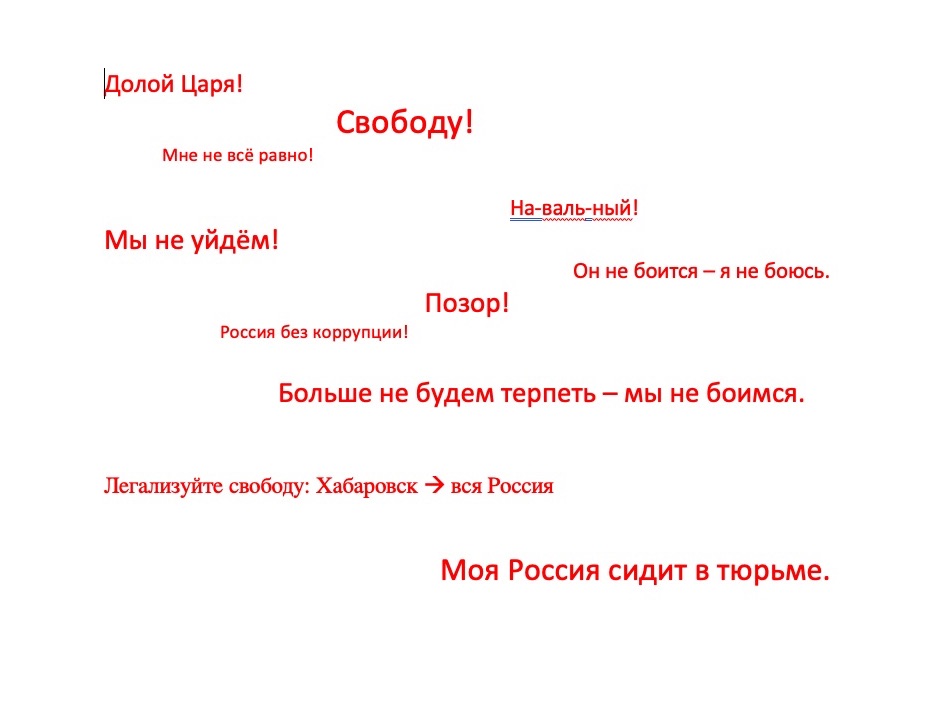

‘Why won’t you release him?’ the woman in Saint Petersburg asked the policeman. He kicked her in the stomach.

On Saturday, Russians gathered to protest in cities across eleven time zones. They waved toilet brushes and blue underpants. A toilet brush in Putin’s palace was said to cost 700 euros. The poisoned underpants were meant to kill Navalny.

Protestors threw snowballs at riot police.

Down with the Czar

Freedom!

It’s not all the same to me.

Na-val-ny!

We are not leaving.

He is not afraid – I am not afraid.

Shame!

Russia without corruption.

We will not put up with this any longer – we are not afraid.

Legalise freedom: Khabarovsk all Russia.

My Russia sits in jail.

Over a megaphone a recorded message droned on:

‘Уважаемые Граждане, данное мeроприятие незаконное’.

Dear citizens, this event is illegal.

Today, Monday 25 January, is the birthday of the Scottish poet Robert Burns. His poem ‘Is There for Honest Poverty’ seems to fit the day as I watch footage of the protests in Russia, wondering, worrying, but full of admiration and hope and joy at those snowballs. I called my cousin Shane who often gives the address to the haggis on Burns’ Night and asked him to recite the poem. He sang it instead. ‘Gowd’ is gold. ‘Coof’ or cuif is a dolt, a fool. ‘Aboon’ is above. ‘Shall bear the gree’ is ‘have the first place.’ Glossaries for the Scots and Marshak’s popular Russian translation are easily found online.

The other poem that comes to mind is Osip Mandelstam’s epigram to Stalin, or the ‘Kremlin Highlander’ with his plump fingers, and the kicking he gives at the end.

Is there for honest Poverty

That hings his head, an’ a’ that;

The coward slave-we pass him by,

We dare be poor for a’ that!

For a’ that, an’ a’ that.

Our toils obscure an’ a’ that,

The rank is but the guinea’s stamp,

The Man’s the gowd for a’ that.

What though on hamely fare we dine,

Wear hoddin grey, an’ a that;

Gie fools their silks, and knaves their wine;

A Man’s a Man for a’ that:

For a’ that, and a’ that,

Their tinsel show, an’ a’ that;

The honest man, tho’ e’er sae poor,

Is king o’ men for a’ that.

Ye see yon birkie, ca’d a lord,

Wha struts, an’ stares, an’ a’ that;

Tho’ hundreds worship at his word,

He’s but a cuif for a’ that:

For a’ that, an’ a’ that,

His ribband, star, an’ a’ that:

The man o’ independent mind

He looks an’ laughs at a’ that.

A prince can mak a belted knight,

A marquis, duke, an’ a’ that;

But an honest man’s aboon his might,

Guid faith, he mauna fa’ that!

For a’ that, an’ a’ that,

Their dignities an’ a’ that;

The pith o’ sense, an’ pride o’ worth,

Are higher rank than a’ that.

Then let us pray that come it may,

(As come it will for a’ that)

That Sense and Worth, o’er a’ the earth,

Shall bear the gree, an’ a’ that.

For a’ that, an’ a’ that,

It’s comin yet for a’ that,

That Man to Man, the world o’er,

Shall brothers be for a’ that.

[1795]

January 19 to January 26

January 12 to January 19

January 5 to January 12

The Sound of the Light

Although it is only the beginning of January the end of last year has fallen away abruptly. I am still tying up bits and pieces from last year, bracing myself for the weeks or months of uncertainty with the virus spreading faster than ever in my city, and another lockdown. The political failures are depressing but not worth dwelling on here, or anymore. The Crown Letter is different: a gift, a correspondence, a gathering of possibilities – happily the best of last year is carrying on into this one.

I made this recording ten days ago for a friend’s radio broadcast, Thinking Through Light, about artists working with light, to send out a burst of optimism and hope for the coming year. You can hear the whole broadcast here, about 30 minutes in: https://www.mixcloud.com/Resonance/bad-punk-27-december-2020-thinking-through-light-1/

I’d like to hold on to the feeling of walking against the wind and the relief when I turn around to lean on it, the shrill insistent alarm call of oyster catchers, the crusty frozen mud under my boot and the crack and squelch when I break through the ice on a puddle.

December 15 to December 22

December 8 to December 15

The temperature has dropped. It is close to freezing and a fog hung outside my window this morning. It was a watery indecisive mist, not a heavy blanket, not the kind that muffles the street sounds. I turned on the flashing lights on my bike to make sure I didn’t disappear. Wearing a cloth face mask trapped my warm breath, a moist cocoon.

My filmed horizons this week are all watery. Watery horizons often seem full of promise, longing, and sometimes danger. Some of these horizons are arctic, but not wintry. There is no ice, though a dusting of snow on Sakhalin. The water is mostly in motion – water churned by waves, wind, tides, river currents, motors and other boats. There is a glimpse of Crimea – a southern dream from Russia’s north. And the polar summer night shimmers into day on the White Sea coast.

A friend told me that a pan from left to right is meant to suggest that something is going to happen.

I dream of stringing together horizons across the globe, like bunting made by many people, each view waving the next one in. I can lose myself quite happily looking outward, and forget the inward gaze for a time.

Please keep sending me your horizons (see week 29, November 11-18, for details).

December 1 to December 8

Please keep sending me your horizons (see week 29, November 11-18, for details).

November 24 to December 01

November 17 to November 24

The hand-held panning shot is a risky one, as one is bound to trip over a root, or speed up or slow down as one tries to steadily revolve like a lighthouse shining a beacon for ships passing by through dangerous waters.

Receiving video clips this week has been like receiving postcards from far flung places but more mysterious. What is hidden in plain view here? What was going through the mind of the person filming? What if anything is happening? Even the views that I filmed myself don’t reveal themselves to me.

This is my first attempt at sewing together the footage I have been sent into a rolling horizon. It is silent for now. Sounds may come later. I’ve been promised some.

Please send me more clips. You can send me a message on Facebook, or Instagram, or email the Crown Letter.

The space between us seems to ripple, or fold, or maybe unfold.

November 10 to November 17

Horizon – the space between us

I would like to invite you to help create a collective film.

A second wave of the Coronavirus pandemic is causing governments to introduce lockdowns again. I feel my horizons simultaneously shrink to the size of my neighbourhood, and expand as my thoughts and dreams are filled with events far away. On Saturday night I wished I were dancing in the street in New York or Philadelphia. Instead I raised a glass with my next door neighbours over the garden wall, which was also a delight.

The rifts between people seem especially deep right now. But maybe others share this feeling of shrunken and overstretched horizons, whatever their immediate surroundings, fears or disappointments. Forest fires, floods, empty streets, streets full of protests, or celebrations, or both, long, socially-distanced lines at polling stations or banks, an iceberg floating in the Antarctic Ocean – all these scenes have been happening before our eyes.

I would like to create a collective, continuous – potentially infinite – landscape film, to see if our horizons can join up. I would like to see what happens when we follow a horizon line. For a first experiment, a first shared horizon, I’d like to invite the Crown Letter artists (and their friends) to contribute. The instructions are simple:

Use whatever device you have to hand (a phone or a video camera), hold it horizontally and find a horizon line. It can be just a line – a break between up and down, foreground and background. Holding the camera steady (in your hand will do, or on a tripod), slowly pan from left to right, or right to left. Try, if possible, to begin and end your clip with a dividing line visible in the middle of the shot – the horizon.

The horizon needn’t be a distant view of hills or sea, or buildings, or sky – your landscape can be your kitchen shelf, the kerb, a leaf or rock. Your interior or internal landscape is perhaps the nearest to hand, the most vivid, the horizon that holds your attention right now.

Please send me your clips – between 5 and 30 seconds – and I will sew them together. You may include sound or not, or record sound separately. Please send a few words to accompany your moving images, and include your location. Thank you.

November 3 to November 10

An extended interruption

I can’t see anything clearly right now. Not because of a lack of clarity on my part, though there may be, but because of the suspense of the past days and nights and those around the corner. Last week I didn’t send a Crown Letter, though I filmed this week’s film. So this week’s is really last week’s, though I see it differently now.

I feel caught mid-sentence, mid-thought, mid-breath, in an extended interruption. The US election is tomorrow although 90 million people have already voted, including me. The result may not be decided for some time (by whom?). The suspense and the possibility that Trump could win again is excruciating. The suspense is nothing compared to the nearly guaranteed destructiveness of this single person continuing in power. The suspense has leached into everything. Or rather, there are multiple concurrent tragedies that are a cause for suspense, uncertainty, fear and sorrow, and an overload of dread: the brutal attacks on a teacher and a priest – people who live to help others – the exponential spread of Coronavirus, and the acceleration of warming and methane release in the Arctic. It is much too much to go into here or all at once, and yet it is all happening at once. Instead we try to be productive or get on with work or domestic life, to think about other things for a time and distract from the gloom, and the wait.

I look forward to the Crown Letters this week, and to sharing the grief and suspense.

October 20 to October 27

October 13 to October 20

October 6 to October 13

Saint Terre

‘When we walk, we naturally go to the fields and woods: what would become of us, if we walked only in a garden or a mall?’

Henry David Thoreau

The current campaign to stop the building of a train line – known as High Speed 2 or HS2 – through ancient English woodland, to connect cities that are already connected by train lines, reminds me of the destruction of woodland by developers who built on the beach next to Walden Pond in Concord Massachusetts. This was where Henry David Thoreau lived for a while in a hut he built himself. I grew up hearing about this story. A legal case was brought against the developers and failed, was appealed and won. The developers were obliged to remove the buildings and restore the habitat as far as possible to its original ‘natural beauty’. Judge Cutter who wrote the decision was my grandfather.

Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts, Middlesex.

John E. NICKOLS et al. v. COMMISSIONERS OF MIDDLESEX COUNTY. Eleanor T. MOORE et al. v. COMMISSIONERS OF WALDEN

POND STATE RESERVATION et al.

Argued March 11, 1960, |Decided May 3, 1960.

September 29 to October 6

Annihilation of Caste – an undelivered speech by Dr. B. R. Ambedkar

The exhibition ‘Ideas Travel Faster than Light’ curated by Clair Joy and Jasone Miranda-Bilbao, is the second exhibition in which a group of artists in one country give instructions to another group of artists. This time, artists from India gave instructions to artists from Canada, USA and Spain.

I was asked to collaborate with the artist Jogesh Barve. He asked me to read aloud Annihilation of Caste by B. R. Ambedkar. Ambedkar was a social reformer, first minister of Law and Justice and principle author of the Constitution of India. He inspired the Dalit Buddhist movement and campaigned against discrimination against the so-called Untouchables or ‘depressed classes’. He wrote the speech in 1936 but was unable to deliver it because it ruffled too many feathers. It is an indictment of Hinduism and the Caste system in India. Although he specifically attacks the Hindu caste system and its defenders, his painstaking and ferocious dismantling could apply to many other systems of class, caste and racial discrimination. Ambedkar published the speech and it became hugely influential. Recently it has been picked up again internationally – its ideas on caste applied to race and class, in the context of the US and Britain. Ambedkar studied at the London School of Economics in the 1920s, not far from Mecklenburgh Square. He wrote that his years in London and New York were a release from the prejudices he experienced in India.

On Saturday 26th September, on a cold and windy day in Mecklenburgh Square in Bloomsbury, with the help of friends, I read aloud the entire text of the undelivered speech. The rhetorical rhythms of the speech make it roll off the tongue, although we did sometimes stumble over the Sanskrit couplets and references to contemporary thinkers and writers. At times I felt Ambedkar was speaking through us (which he was) and that the speech was addressed not just to his audience but to unwilling audiences everywhere: to all the establishment hypocrites afraid of losing their power and privilege, and to those afraid of rocking the boat, from all times and places. It certainly made me want to rock it more. There was an uncomfortable passage where he talks about Eugenics, which in the 1930s was mainstream science, and I had to snap out of the speech and talk about it with the audience. At other times, I felt hopeful and assured that with such an ally, justice could be achieved, and would be.

This is a tiny extract.

September 22 to September 29

Memory Retrieval Systems

I made this poster nineteen years ago. This was before bleeps on your mobile phone reminded you of appointments or your to do list, before social media websites regurgitated past posts to remind you of your digital life. The poster brings together forms of memory that are vastly different in scale, purpose and context. The Venn diagram is not random, though I now can’t remember my precise reasoning for the layout. Some categories, such as ‘soft systems methodology’ and ‘data management’ seem like ugly words I was holding with tongs not to be contaminated or seduced by their bureaucratic and machinic logic. They seem fairly benign and almost everyday now; while memex is a forgotten historical curiosity, like quipu. Some words are still incredibly scary, or have become infinitely more so recently: forgeries and fakes, surveillance, and especially, virus.

Memories apparently are not lost from our brains, while we live, but can become hard or impossible to reach. Revisiting this poster, I sense my desire to enjoy, reflect on and admire the richness, variety and intricacy of the inventions people have made to help remember and perpetuate a culture. Some of the words are almost magical in their ability to conjure a better world: the architectural strength of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the benevolent social role of bards, and the poetry of songlines especially. I think I was being tugged in another direction too, perhaps more strongly, by the disembodied memory retrieval systems that gather information but don’t enhance or expand human possibility, but instead destroy people, and places. I am struck by how little allusion there is to the natural world, except for the Songlines, but perhaps that isn’t surprising as this was a work researched and made in an archive, underground, with no windows.

I made this poster for my exhibition, The Archives Project, and for the exhibition, Potential: Ongoing Archive at John Hansard Gallery, while I was Leverhulme artist in residence in the Archives of the London School of Economics, in 2001-2.

Design: Nicole Kapitza

September 15 to September 22

The turbulence of recent weeks throws me forward, and backwards – planning new projects and reflecting on past ones. So many postponed deadlines from the last six months are now landing with a thud this September. I am trying to keep on an even keel. Maritime metaphors are comforting and frequent, in English, perhaps paradoxically because they also suggest freedom and escape rather than stability. Here, sitting at my desk looking from this big island, I think about a little far away island in the North Sea, Fair Isle. You can walk the length of it in a morning, and it is indeed very fair. It is quite hard to leave and to arrive, because of the weather conditions. Sometimes the little islands of Britain however are better connected to the rest of the world than the so-called mainland.

Yesterday I was told by a friend who lives there, about how another island, Hong Kong, is greeting travelers. If you arrive at the airport, you are tested, and given a sandwich and a bottle of water and have to wait until the result is ready, about 14 hours. Then, if the test is negative, you are allowed to go home and self-isolate. However you must download a special app, and when you get home you must walk around the edge of your apartment recording it on the app. Once this is registered, you are not allowed to go beyond the perimeter of your home until your quarantine is over. Any breach of this will be noted.

I have started reading Helen Macdonald’s new collection of essays, Vesper Flights. She speaks of the need to recognise and appreciate the otherness of other animals. We need this more than ever, not just to respect otherness but to enjoy and wonder at the complexity of a world where so many different kinds of living things rub up against each other. She describes moments of extraordinary connection between different species, for instance when she met a boar for the first time, and another when a young boy communed and danced with her parrot. This reminded me of an encounter I filmed, almost by accident, on the island of Fair Isle, in late August, 2013. A rather overfed fulmar chick sits too close to the side of the road, unable to fly yet, because of its youth, and girth. A curious black lamb, maybe six months old, approaches to inspect it, and then comes to inspect me. I with my tripod and camera play a role, as does a passing car. The little comedy unfolds before and with the camera, and my memory of our meeting was immediately confused with the film, which until now was left unmade.

September 8 to September 15

September 1 to September 8

Test centre

I woke up with a head of concrete, someone banging on it; and more concrete on my belly. It came on suddenly, and didn’t subside. I couldn’t eat. Robin called work to let them know he might not be able to come in. Work insisted he couldn’t come in for two weeks, and the whole family would have to self-isolate, if we didn’t take the test. I took my temperature, with the dodgy digital thermometer which insists we are a cold family – having temperatures of 35.5. Except for the day last year when the youngest held the thermometer against the towel rail. It reached 48 degrees. I gave him Calpol and sent him to school. But this time I had a temperature higher than normal for a little while.

I spent the second day, still whoozy, hunting down symptoms and apps and calling the National Health Service numbers 111 and 119, listening to the new bot Olivia mouthing a questionnaire and trying to reassure with her strangely animated facial muscles. It felt obscene listening to a bot ask questions about intimate body parts, not reacting at all. She speaks in a placeless, ageless middle class senior nurse – a sister or matron – accent designed to convey authority, with understanding. But her awkward facial muscles suggested a certain unease or lack of confidence. She wore a necklace for some reason – I thought nurses weren’t meant to wear jewellery as it could hurt someone or catch on an apron, or the thread could break and the beads spill all over the floor of the ward and someone might trip and fall and pull the cord on a life support machine… But Olivia wore a necklace. I was eventually advised to contact my doctor’s surgery immediately, and was put through by Olivia, or the app’s receptionist. I was impressed when Olivia got me through to without a wait. She obviously has some clout. The receptionist wearily informed me that there were no appointments to be had. She sounded astonished that I would think there might be. I’d need to ring at 8am the next day to make an emergency appointment, which wouldn’t be an appointment but rather I’d leave my number and a doctor would call back, and talk to me about my symptoms and then possibly invite me to a real place, but not the surgery, if I needed to be seen. I knew it would be a long wait in a phone queue – there are often up to twenty people ahead even if you ring on the dot of 8.

I tried another tack. I downloaded the Coronavirus symptom checker app. I didn’t think I had the virus as my symptoms were different. However Robin needed to go to work, and we all want the boys to be able to go to school, so my fleeting high temperature was the symptom I held on to, and let it guide me through the app questions, filling in the online form to try to order a home Covid test. It crashed five times, at the very end of the process, by which time I could barely remember my own name. I was sick after all. So I rang a number and spoke to a real person. I know he was real because he slipped off script easily, and told me that he was doing the same as I was and that there weren’t enough tests because demand had sky-rocketed last week, so they were releasing test slots every hour so as not to use them all up at the beginning of the day (thereby keeping sick people on the app and phone all day wondering what was up, or whether they were mad, or just hopeless). He told me to keep trying. I went to bed and fell asleep. Two hours later I woke up and tried the app, and booked a test for me and Robin at the nearest test centre in Billingsgate fish market in Canary Wharf.

I made a film here twenty years ago, Billingsgate, when most of the buildings weren’t built yet, drawing on Marx and Engels’ analysis of the nature of the commodity and the exploitation of labour in capitalism. The Market and the market. Fish are a slippery commodity of course – they spoil quickly.

Canary Wharf – that looming glass citadel and symbol of global corporate capitalism – and the fishy stink of Billingsgate seem the perfect setting for a drive-by Coronavirus testing centre.

August 18 to August 31

August 4 to August 11

Red Campion, Clover and Angelica

I waded through the nettles at the cliff-edge,

Elbows forward, hands held up above the Thistle spears

On a mission to gather as many flowers as I can hold this windy morning

To lay upon my father’s fresh new grave tomorrow.

Blood red Dock leaves spread beneath their scabby flowers,

Fluffy Meadowsweet sweetly envelops as I sniff and sneeze,

Pale-pink Ragged Robin flutters in a ditch,

Knapweed thistle goblets push through the taller stalks;

Yellows and purples don’t mix,

Just spot the swathes of grass-green, dust-grey, ochre.

Tufted Vetch – bouncing arabesques of dark blue,

Red Campion – bright carmine flags,

Waving crowns of Red Clover,

Each bud covered with a bee or bug

Clinging to sweetness against the wind.

A Little-Blue pauses, slowly flapping,

While other butterflies blow about in gusts.

Little yolk-yellow bubbles of Bird’s Foot Trefoil huddle at my feet;

Around the crumbled edge,

The cliff-crack softened by the grass, Clover, Buttercup and Vetch,

My eye wanders, caught by unfamiliar flowers, like weird wild Angelica, with its

Prehistoric bulbous sepals and cauliflower heads.

My careful clumping boot suddenly drops down a deeper furrow,

A wrinkle formed in land released, rebounding,

Now the last glacier’s melted;

The island still keeling, tipping skyward;

And the sea, warmed, rising, crashing against the sandstone slab.

Purple-red Self-Heal, pale-domed Harebell and floating Fairy flax,

Lamp-yellow daisy-heads of Goldenrod,

And softer yellow powder-puffs of Lady’s bedstraw mingle at my feet.

Across the ditch, up onto the headland, the grass falls away,